The ability of satellites to communicate directly with each other represents one of the most sophisticated achievements in modern space technology. While most people understand that satellites transmit data to and from Earth, the complex systems enabling satellites to relay information between themselves in the vacuum of space remain less familiar. This inter-satellite communication capability, often called crosslink technology, fundamentally transforms how satellite networks operate, enabling global connectivity, reducing reliance on ground infrastructure, and improving data transmission efficiency. Understanding how satellites accomplish this remarkable feat requires exploring the physics, engineering, and operational strategies that make space-based data networking possible.

The Fundamental Challenge of Space Communication

Communicating between satellites presents unique challenges that differ substantially from terrestrial wireless communications or even satellite-to-ground links. The space environment imposes constraints that require specialized solutions and sophisticated technology.

Distance represents the first obvious challenge. Satellites in low Earth orbit might be separated by hundreds or thousands of kilometers, while satellites in different orbital planes or altitudes can be even farther apart. Transmitting data across these vast distances requires powerful transmitters, sensitive receivers, and precise pointing systems to establish and maintain connections.

The vacuum of space eliminates atmospheric interference that affects terrestrial communications, which seems advantageous. However, it also means signals cannot benefit from atmospheric reflection or scattering. Line-of-sight becomes absolutely critical, as signals cannot bend around obstacles or propagate through diffraction as they can in Earth’s atmosphere. If one satellite cannot directly “see” another, communication becomes impossible without relay intermediaries.

Orbital dynamics create constantly changing geometries between satellites. Objects in low Earth orbit travel at approximately 7.5 kilometers per second, meaning the relative positions of satellites change continuously. Communication systems must track moving targets, adjust pointing directions, compensate for Doppler shifts in signal frequency, and hand off connections as satellites move in and out of range. This dynamic environment demands sophisticated control systems.

Power limitations constrain communication system design. Satellites generate electricity through solar panels, providing limited power budgets that must support all onboard systems including communications, station-keeping, thermal control, and payload operations. Communication systems must achieve their objectives while consuming reasonable power, creating constant tradeoffs between transmission power, data rates, and energy efficiency.

Thermal management presents another challenge. Electronics generate heat during operation, but the vacuum of space prevents convective cooling. Satellites must radiate excess heat through carefully designed thermal systems. High-power communication systems generate significant heat requiring effective thermal management to prevent equipment damage and ensure reliable operation.

Radio Frequency Inter-Satellite Links

Traditional inter-satellite communication relies on radio frequency transmissions similar in principle to terrestrial wireless communications but adapted for the unique space environment. These RF crosslinks have served satellite communications for decades and continue evolving to meet increasing performance demands.

Radio frequency systems transmit data by modulating electromagnetic waves at frequencies typically in the Ka-band around 26 to 40 gigahertz or the Ku-band around 12 to 18 gigahertz. These relatively high frequencies enable higher data rates and more compact antennas compared to lower frequencies. The choice of frequency band involves tradeoffs between data capacity, antenna size, atmospheric attenuation for ground links, and regulatory considerations.

Antenna systems for RF inter-satellite links must combine several capabilities. They need sufficient gain to concentrate transmitted power and collect weak received signals across vast distances. They require steering mechanisms to point at target satellites as orbital positions change. Many systems use phased array antennas that electronically steer beams without physical movement, enabling rapid repointing and the ability to communicate with multiple satellites simultaneously.

Modulation schemes encode data onto radio carrier waves using various techniques that balance data rate against robustness to noise and interference. Modern satellites employ sophisticated adaptive modulation that adjusts encoding complexity based on link quality, maximizing throughput when conditions are good while maintaining connectivity when signal quality degrades. Forward error correction adds redundancy that enables receivers to detect and correct transmission errors without requiring retransmission.

Power amplifiers boost transmitted signals to levels sufficient for detection across inter-satellite distances. These amplifiers represent significant components of satellite power budgets and contribute substantially to thermal loads. Traveling wave tube amplifiers and solid-state power amplifiers each offer advantages depending on power requirements, efficiency priorities, and reliability considerations.

Receivers employ sensitive low-noise amplifiers and sophisticated signal processing to extract data from weak received signals. The signal-to-noise ratio determines achievable data rates, creating fundamental physics limitations that drive antenna size, transmit power, and link distances. Engineers constantly work to improve receiver sensitivity and signal processing algorithms to push performance boundaries.

Data rates achievable through RF inter-satellite links range from megabits to hundreds of megabits per second depending on system design, distance, and performance priorities. While impressive, these rates increasingly struggle to meet bandwidth demands of modern applications, motivating development of alternative technologies.

Optical Inter-Satellite Links

Laser-based optical communication represents the cutting edge of inter-satellite data transmission, offering dramatic performance improvements over radio frequency systems. These optical inter-satellite links, sometimes called laser crosslinks or optical crosslinks, enable data rates orders of magnitude higher than RF systems while using less power and smaller terminals.

Optical communication transmits data by modulating laser beams typically in infrared wavelengths around 1,550 nanometers, the same wavelengths used in terrestrial fiber optic communications. This commonality allows leveraging mature fiber optic component technology including lasers, optical amplifiers, and photodetectors developed for ground-based networks.

The fundamental advantage of optical communication stems from much shorter wavelengths compared to radio frequencies. Optical wavelengths measure hundreds of nanometers while radio wavelengths measure centimeters to meters. This wavelength difference enables several critical improvements. First, diffraction-limited beam divergence decreases with shorter wavelengths, allowing extremely narrow laser beams that concentrate transmitted power more effectively than radio signals. Second, shorter wavelengths enable higher modulation bandwidths and thus higher data rates. Third, compact optical systems achieve antenna gains requiring much larger radio frequency antennas.

Pointing accuracy requirements for optical links are extraordinarily demanding. Laser beams between satellites typically diverge to only microradians, creating spot sizes measured in meters across inter-satellite distances of thousands of kilometers. Pointing errors of even microradians can cause the beam to miss the target satellite entirely. Achieving this precision requires sophisticated acquisition, tracking, and pointing systems combining coarse mechanical steering with fine-pointing mirrors and highly accurate sensors.

The acquisition process for establishing optical links involves several stages. Initially, satellites use radio frequency or GPS data to determine approximate relative positions. Coarse pointing directs optical terminals toward expected target locations. Wide-angle beacon lasers help satellites locate each other during initial acquisition. Once detected, narrow tracking beams enable fine pointing refinement. Finally, high-power communication beams activate to transmit data. This multi-stage process ensures reliable link establishment despite extreme pointing precision requirements.

Data rates achievable through optical inter-satellite links can exceed multiple gigabits per second, with some advanced systems demonstrating tens of gigabits per second. These rates dwarf traditional radio frequency capabilities, enabling satellites to relay enormous data volumes. Earth observation satellites generating terabytes of imagery daily can downlink this data through optical crosslinks far faster than through individual ground stations.

Power efficiency represents another optical advantage. While peak power during transmission pulses can be high, average power consumption remains relatively modest compared to continuous-wave radio transmitters achieving similar data rates. The narrow beam confinement also provides inherent security advantages, as intercepting optical signals requires positioning precisely within the narrow beam path.

Network Topologies and Routing

How satellites organize their inter-satellite communications significantly affects network performance, reliability, and complexity. Different constellation architectures employ various networking approaches optimized for their specific missions and orbital configurations.

Mesh networks where satellites can communicate with multiple neighbors provide maximum flexibility and resilience. Each satellite maintains links to several adjacent satellites in its orbital plane and potentially to satellites in neighboring planes. This connectivity mesh enables data to route through multiple possible paths, automatically flowing around failed satellites or congested links. However, mesh networks require more complex routing algorithms and increase system complexity since each satellite needs multiple crosslink terminals.

Linear or string topologies connect satellites in sequential chains, typically along orbital planes. Each satellite communicates with satellites immediately ahead and behind in its orbit. This simpler topology reduces hardware requirements since satellites need only two crosslink terminals. However, it creates single points of failure where one satellite failure can break the chain, and it constrains routing flexibility compared to mesh architectures.

Hub and spoke models designate certain satellites as relay hubs while others only communicate with hubs. This hierarchy simplifies routing and reduces the number of crosslinks required, but it creates bottlenecks at hub satellites and single points of failure if hub satellites fail. Some military and government satellite systems employ this topology to centralize control and reduce network complexity.

Routing protocols determine how data packets navigate through satellite networks. Static routing uses predetermined paths calculated based on orbital mechanics and network topology. While simple and predictable, static routing cannot adapt to failures or congestion. Dynamic routing protocols continuously assess network conditions and adjust paths to optimize performance and avoid problems. However, dynamic routing requires satellites to exchange routing information and make autonomous decisions, increasing software complexity and processing requirements.

Latency through multi-hop satellite networks depends on path length, processing delays at each satellite, and propagation delays between satellites. Each satellite in a path introduces processing delays for receiving, routing, and retransmitting data. Optical signals propagate at light speed, taking roughly 3.3 microseconds per kilometer. For inter-satellite distances of 2,000 kilometers, propagation delay alone contributes about 6.6 milliseconds. Multi-hop paths accumulate these delays, though they often remain competitive with terrestrial routes covering similar geographic distances.

Processing and Switching Aboard Satellites

Modern satellites must perform sophisticated onboard processing to support inter-satellite communications effectively. These processing capabilities transform satellites from simple relay stations into intelligent network nodes capable of autonomous operation.

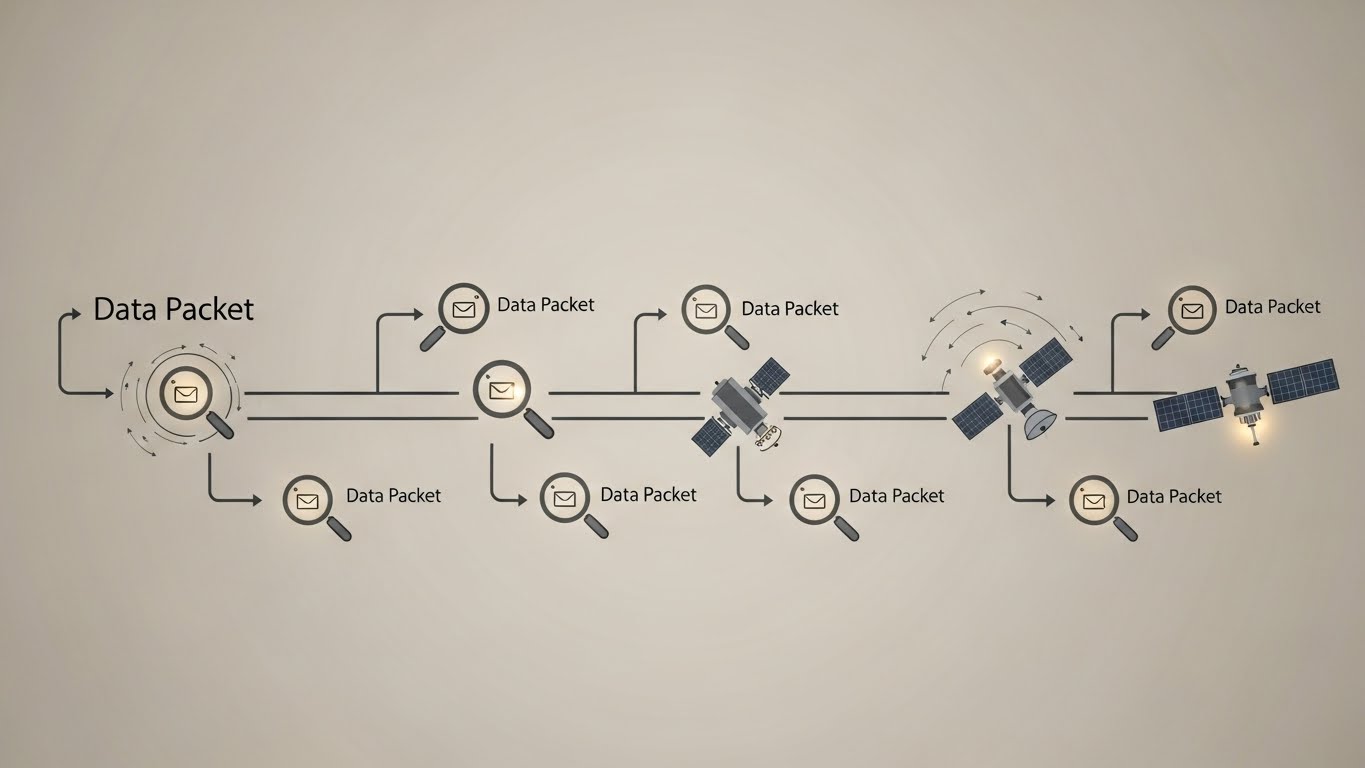

Packet switching examines data packet headers to determine appropriate routing paths and forwards packets toward their destinations. This requires satellites to maintain routing tables, make forwarding decisions, and queue packets for transmission on appropriate outbound links. The processing hardware must handle these operations at data rates potentially reaching multiple gigabits per second, demanding capable processors and specialized routing hardware.

Quality of service mechanisms prioritize different traffic types to ensure critical data receives preferential treatment. Satellites may implement traffic classification, priority queuing, and bandwidth allocation policies that maintain performance for high-priority communications even when network capacity is constrained. These capabilities enable satellite networks to support diverse applications with varying performance requirements simultaneously.

Error handling and retransmission protocols compensate for data corruption or packet losses during transmission. Satellites may implement automatic repeat request mechanisms that detect errors and request retransmission of corrupted packets. Forward error correction adds redundancy enabling receivers to correct errors without retransmission. The optimal balance between these approaches depends on link quality, latency sensitivity, and throughput requirements.

Protocol translation capabilities allow satellites to interface between different communication standards. Ground stations may use different protocols than inter-satellite links, requiring satellites to translate between protocols. This translation functionality enables satellites to serve as bridges between terrestrial internet infrastructure and space-based networks.

Onboard storage provides buffering for data that cannot immediately transmit due to link unavailability or capacity constraints. Satellites may store data until appropriate communication opportunities arise, then forward stored data when links become available. This store-and-forward capability enhances network resilience and enables satellites to serve as data mules carrying information between disconnected network segments.

The computational requirements for these processing tasks demand capable spacecraft computers with sufficient processing power, memory, and radiation-hardened reliability. Recent satellites increasingly employ more powerful processors and even commercial-off-the-shelf components hardened for space applications, enabling more sophisticated onboard processing than heritage systems.

Timing and Synchronization

Precise timing synchronization across satellite networks enables efficient communication and accurate positioning services. Multiple mechanisms ensure satellites maintain synchronized clocks despite orbital dynamics and relativistic effects.

Atomic clocks aboard satellites provide stable time references with accuracy measured in nanoseconds. These clocks, similar to those used in GPS satellites, maintain time standards despite temperature variations and radiation exposure. High-quality atomic clocks cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and consume significant power, so not all satellites carry them. Instead, some satellites synchronize to atomic clocks aboard designated master satellites or ground stations.

Relativistic effects must be accounted for since satellites travel at high velocities and experience different gravitational fields than ground stations. Special relativity predicts that moving clocks run slower, while general relativity predicts that clocks in weaker gravitational fields run faster. These opposing effects partially cancel for low Earth orbit satellites but still require compensation for precision timing applications.

Network time protocols synchronize satellite clocks through message exchanges that measure and compensate for propagation delays. Satellites exchange timing messages and use the round-trip time to calculate clock offsets and adjust their local clocks accordingly. These protocols must account for asymmetric delays where forward and return paths take different times.

Doppler compensation adjusts for frequency shifts caused by relative motion between satellites. When satellites move toward each other, received frequencies increase, while motion apart decreases frequencies. Communication systems must measure and compensate for these shifts to maintain proper signal reception. Doppler shifts in low Earth orbit can reach tens of kilohertz, requiring active tracking and compensation.

Operational Considerations and Challenges

Operating inter-satellite communication networks requires addressing numerous practical challenges that affect reliability, performance, and cost.

Sun interference occurs when the sun aligns with inter-satellite links, overwhelming sensitive receivers with solar noise. These sun outage events can disrupt communications for minutes or hours depending on geometry. Network operators must predict sun interference windows and route traffic around affected links during outages. Optical links are particularly sensitive to sun interference since sunlight occupies similar wavelengths.

Eclipse transitions as satellites enter and exit Earth’s shadow cause thermal cycling that can affect equipment calibration and performance. Communication systems must remain operational through these temperature swings while maintaining pointing accuracy and signal quality. Thermal design and operational procedures compensate for eclipse effects.

Collision avoidance maneuvers performed to dodge orbital debris or other satellites can temporarily disrupt inter-satellite links as satellites change orbits and relative geometries shift. After maneuvering, satellites must reacquire communication links and resynchronize timing. Frequent debris avoidance maneuvers increasingly complicate network operations as the orbital debris population grows.

Radiation effects accumulate as satellites spend years in space exposed to charged particles, solar radiation, and cosmic rays. These radiation doses can degrade electronic components, cause bit flips in memory, and eventually lead to failures. Communication systems must employ radiation-hardened components and error correction mechanisms to maintain reliability throughout mission lifetimes.

Software updates and patches must occasionally be uploaded to satellites to fix bugs, improve performance, or add capabilities. Updating satellite software requires careful testing since failures could render satellites inoperable with no possibility of physical repair. Inter-satellite links provide paths for distributing software updates across constellations, though this capability introduces cybersecurity considerations.

Future Developments and Emerging Technologies

Inter-satellite communication technology continues advancing rapidly with several promising developments on the horizon.

Higher data rate optical links will employ advanced modulation formats, wavelength division multiplexing, and improved optical amplifiers to achieve tens or hundreds of gigabits per second. These rates will enable satellites to function as true space-based internet routers handling internet-scale traffic volumes.

Free-space quantum communications may enable absolutely secure key distribution between satellites using quantum entanglement. While still largely experimental, quantum communication through optical links could provide communication security guaranteed by physics rather than computational complexity.

Optical mesh networks with satellites simultaneously maintaining multiple laser links will provide greater redundancy and throughput compared to current systems. However, they require satellites to carry multiple optical terminals, increasing cost, complexity, and power consumption.

Inter-orbit links connecting satellites in different orbital regimes could bridge low Earth orbit constellations with geostationary satellites or provide connectivity to deep space missions. These links must accommodate larger distances and relative velocities than links between satellites in similar orbits.

Software-defined networking approaches will enable more flexible and adaptive satellite networks. Reconfigurable systems can adjust link capacities, routing strategies, and resource allocation dynamically in response to traffic demands and network conditions.

Conclusion

Data transmission between satellites represents a remarkable technological achievement enabling global connectivity, reduced ground infrastructure dependence, and efficient data relay across satellite networks. Whether using radio frequency systems with decades of heritage or cutting-edge laser communication offering gigabit speeds, inter-satellite links leverage sophisticated engineering to overcome the unique challenges of space communications.

The physics of electromagnetic propagation, the precision of acquisition and tracking systems, the intelligence of onboard processing, and the coordination of network protocols all combine to create functioning space-based data networks. These capabilities transform satellite constellations from collections of independent spacecraft into cohesive networks that operate similarly to terrestrial internet infrastructure.

As technology advances and constellations expand, inter-satellite communications will become increasingly central to satellite operations. The ability to relay data through space routes, optimize network performance dynamically, and provide global coverage without extensive ground infrastructure makes inter-satellite links essential for next-generation satellite services. Understanding how these systems work provides insight into one of the most sophisticated and critical technologies enabling our increasingly connected world.